| 日本語 | English |

![]()

Please refer to ““Tokyo Tech Museum Policies on Viewing and Data Usage”for this site.

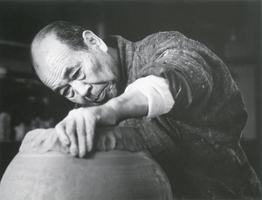

Awaken to the beauty of Mingei, mentored by Shoji Hamada of Mashiko, Tatsuzo Shimaoka established his unique style called ‘Jomon zogan.’

photo:Tsuyoshi INUI

Tatsuzo Shimaoka was born in 1919 as the first son of a braiding artisan in Tokyo. Inspired by the works of Kanjiro Kawai and Shoji Hamada he encountered in the Japanese Folk Crafts Museum as a third year student at high school, he decided to become a ceramic artist. The following year after enrolling in the Tokyo Tech’s Department of Ceramics, he visited Shoji in Mashiko (Tochigi Prefecture) and obtained approval as his post-graduate apprentice. However, his term was hindered by the outbreak of the Pacific War. In 1942 he was drafted to an engineering regiment and sent to Burma, during which time he sustained his passion for pottery by taking a Shino cup with him. He survived the war and returned to Japan finally in 1946 to start his apprenticeship with Shoji.

After being employed for three years by a ceramic training center in Tochigi, he set up his own pottery in Mashiko in 1953 and produced his Hatsugama (first kiln) works in 1954. Encouraged by his mentor to develop his own unique styles, he eventually perfected the Jomon zogan style by amalgamating the techniques of rope-pressing, characteristic of Jomon Pottery, and white clay inlaying (zogan) called ‘Mishimade’ originating with the Joseon ceramic style of Korea. Due to his family legacy of braid-making, his style features the use of silk string braids instead of ropes, which are press-rolled on to the surface of clay to make inlay patterns which are then filled with white clay.

His powerful yet elegant Jomon zogan pieces were highly regarded by visitors to his solo exhibitions held both in and outside Japan. Honoring his ceaseless devotion to upholding the spirit of Mingei throughout his works, and also for sharing his expertise with other artisans and budding ceramic artists, the Japanese government conferred on him the title of ‘Holder of Intangible Cultural Properties of Japan’ (in the Jomon zogan style, ceramic art field) in 1996.